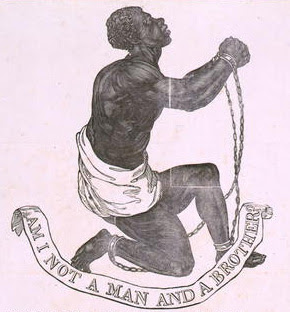

In watching many of the iconic events of the civil rights era on television; James Meredith enrolling in the University of Mississippi; Medgar Evers’ murder; the March on Washington, and the bombing of the Birmingham church that killed four girls, they became part of my own story. Slavery and Public History showed me the shortcomings of my public education, succumbing to the trap of thinking of slavery as an antebellum, pre-Civil War institution. The dichotomy of John Michael Vlach’s story captures the dilemma of public history with the dramatically different responses to “Back of the Big House.” Opposition and support for the project were not divided along racial lines. Neither were the emotional responses. The dialogue that took place from beginning to end demonstrated the best tool for treating such volatile topics.

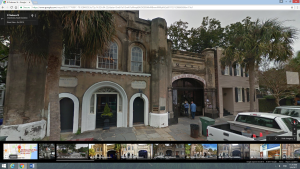

I personally connected to Edward Linenthal’s epilogue. Whether Linenthal was talking about Jim Carrier’s A Traveler’s Guide to the Civil Rights Movement or Richard Rubin’s Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South, I saw my own experiences in their stories of the ordinariness of the places where extraordinary things occurred. I lived in Memphis in 1971, three years after Martin Luther King was assassinated at the Lorraine Motel. I drove by the motel on a couple of occasions. In a dumpy part of town, it was so incredibly ordinary. While on a run around the old city of Charleston I stopped at plaques and historical markers, such as looking out Fort Sumter, or interesting looking antebellum homes. I unexpectedly came across a section of cobblestone street. Looking around I was startled to see a building labeled “The Old Slave Mart.” My first reaction was one of disgust, but when I saw that it was a museum, I looked in the windows and grabbed a piece of literature from the display outside. This former slave auction house, in an otherwise nondescript location, was now a museum.

Screen shot from Google Earth, 2017

Screen shot from Google Earth, 2017

Not every event in history needs to become a NPS site, a museum or have a plaque. However, things which are recognized as important must have the whole story uncompromisingly told. Whether it’s Black Lives Matter or the “law and order” rhetoric, the events of the past year highlight our need to address this story, whether we want to or not.