Month: February 2015

Documentary about “Reading a Building”

It is interesting how things seem more and more interconnected as I learn different aspects of public history. On page 207, a section of chapter 7 is dedicated to “Reading the Building.” In class, we have discussed the Cyrus Jacob Uberuaga house and how just recently, it was discovered that a well was next to the house. Over time, the well had been covered up by a walkway and lost to history for years even though decorative brick work should have been a clue. (Are you proud of me? I figured out how to add media. Try and stop me now!)

It is so easy to look at a building without “seeing” it.

Last week, I happened across a documentary at the library about students from the University of Arkansas who scan famous buildings in order to see how they were constructed, any changes that have occurred over the years, and structural weaknesses that might not be seen by the naked eye. A small scanner collects a billion measurements of a building to form a 3-D model. So besides maps, photographs, and oral histories, there is new technology that helps historians “read” buildings in a scientific way. Don’t worry, there is still a need for nosing around the nooks and crannies of the buildings.

Here is a link for previews: http://www.pbs.org/program/time-scanners/

This link is for the digital scanning program at the University of Arkansas:

This program looks like too much fun and a great way to add a digital component to historical preservation and research. Boise State, take note!

Project planning picture

Historic Preservation

Although I had a lot of the information on federal preservation policy pounded into my head between interning at SHPO, a cultural resource management class here at Boise State , and in the actual process of reaching Section 106 compliance in the historical guard tower reconstruction at Minidoka, I found this a highly engaging piece that covered the basics of preservation pretty well.

Was anyone else blown away that Independence Hall was one of the first examples of American Preservation? I am constantly running across Independence Hall in readings for this class as well as personal reading, and they really do seem to have a lot going for them in terms of setting precedents for historic preservation and interpretation. I was surprised to see how far back that legacy reaches. I think one of my favorite sections of the text was on matching, contrasting, or compatible addition designs. The Church Court Condos and Greenwich Village townhouses were fascinating case studies. I loved the treatment of both, and would find it exciting to live in an apartment with the shell of a historic church built into it, though I think many would easily find this an inappropriate adaptation of a historic structure. I think it is inspiring to see the ways in which the architects considered the historic significance of the townhouse, and symbolically represented it in a compatible design that still stood out. It is never a guarantee, though, that architects will value the significance or context of a building, or that developers will find anything worth saving after considering their impacts through Section 106 compliance. Local examples of this are obvious with the urban renewal that wiped out Chinatown and so many amazing structures. A contrast, then, would be the Owyhee renovation, which has turned out to be very engaged with the community and uses so many beautiful and original structural and design details.

As an aside, if this interested you in any way I highly recommend Tom Green’s CRM class. It’s a graduate anthro class but it covers all of the history of preservation law, actually navigating the policies, ethics and philosophies of cultural heritage preservation in the US and how it differs in other countries, case studies of Section 106/NEPA/NAGPRA compliance, advice for pursuing careers in federal agencies, etc. Dr. Green used to be the Idaho Deputy SHPO and directed the Arkansas Archaeological Survey so he has a lot of interesting experiences and advice. Really useful stuff, hoping it comes in to use for me someday in the future.

That said, I really do enjoy the idea of working in preservation. Reading this stoked an old flame and kind of got my wheels turning. I even started googling historic preservation professional certificates. As much as I want to be done with school forever, things like preservation, conservation, archiving, etc. seem to involve such specific, technical skill sets that you can’t really learn unless you’re in a practicum/field work type situation. Similar to Michelle, it is pretty disconcerting to think I would have to do an additional MA or MS to have enough of a practical background in preservation to be employable. Architectural history seems pretty simple to study, and could be condensed into a short course. Most of the styles here in Idaho I’ve picked up just by reading NRHP nominations.I would also like propose a conversation in class to discuss the options for breaking into this field or what exactly one does when working in preservation… Having seen a small corner of what happens at SHPO, it seems like a lot of lobbying, paper pushing, and bureacracy, so not all that appealing. Although that comes from someone hoping to secure employment within the umbrella of Department of Interior…I’d rather be involved in a more hands on way. Not by chaining myself to an old building that is about to be razed, but perhaps in the field working on actual restoration and preservation. Maybe I actually could draw on some of my construction management skills… Another aside, if anyone is really interested in learning more about character-defining features, Secretary of the Interior’s standards for historic preservation, or some really cool examples of different types of properties around the state, I know both Tom Green and SHPO have presentations they do for different agencies/partners/tribes/firms etc.

As far as pres here in Boise, I think the Boise Architecture Project is a very cool initiative. To involve students at such a young age in a public service project that directly benefits the city, and gets them interested in and learning real skills in preservation seems like such a win-win. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve drawn on that resource when I find myself curious about different buildings around the city. It’s interesting to see how things differ between 2010 and now with those “Endangered in Boise” listings, one of the most disconcerting being the Central Addition homes. Right now there is an entire block of Queen Anne houses all boarded up, and I can only think that they’ll end up being razed. Preservation Idaho tried/is trying to raise funds to purchase/preserve them, but they have a long way to go… Check out their site on this here.

Preservation Idaho also considers Minidoka to be a threatened site. Though it is a National Park, meaning any development in the area or using agency funds must follow Section 106 compliance, as many of you noticed not all preservation policy actually has teeth. Since receiving monument, then park status, and recently benefitting from federal grant programs for Japanese American Confinement Sites to restore some of its structures, Minidoka is in very high danger of losing everything. This is because they are currently fighting a huge CAFO, or concentrated animal feeding operation being established within a mile of the park. This could mean nearly 10,000 head of dairy a mile upwind, completely eradicating any visitor experience value and very negatively impacting the ability of the park to serve its mission. Friends of Minidoka and NPS are working together, along with the support of community members, in reaching land trade agreements to move it elsewhere or otherwise mitigating the effect of the CAFO. This has been an ongoing battle for almost 5 years. See what Friends of Minidoka are working on at their website.

Tyler’s book noted that National Historic Landmark nominations can be accessed in person in DC, but you can also access them here in Boise at SHPO’s office. They also have most of them scanned and linked online as PDFs. I actually pull these up on my phone all the time, to tell the poor people around me about the buildings we are in/near/passed on the way to get lunch. Here is a link if you’re interested.

We are the Skyscraper Condemnation Affiliate

Early in Historic Preservation readers are presented with the ideas of Violett-le-Duc who’s preservation philosophy was to restore buildings to a better state than they could have been constructed originally. This reminded me a lot of that old Boy Scout rule my uncle taught me while camping, “Always leave the campground cleaner than you found it.” However, this philosophy is no longer en vogue.

Instead, there are preservationists who boast that they are environmentally sound and that their work benefits local communities. Yet, they also frown upon installing energy efficient windows and actively at those who reuse of historic building’s remains in the construction of new buildings. (p. 16, 117-118).

Sure, it might not be historically accurate to do so, but I think that “remixed” buildings with non-traditional uses have a lot more potential to be helpful to society than these some of these preservationists want to admit.

Even guidelines for building rehabilitation are semi-problematic. “A property shall be used for its historic purpose or be placed in a new use that requires minimal change to the defining characteristics of the buildings and its site and environment.” (p.112) Which, according to Historic Preservation, means that a historic church should be restored for use as a religious bookstore or community space rather than a gym or clothing boutique. What if a gym, clothing boutique, or non-religious business was more beneficial to the neighboring community? What if these non-traditional uses improved neighborhood health or brought more jobs to the area?

I’m not saying, “Let’s pave paradise & put up a parking lot.” What I think I’m trying to say here, is that this book truly is an introductory text. Honestly, I’m getting a sense that the book might be more than a little biased as well. The issues of preservation are far more nuanced than Tyler & Co. are presenting here. Does anyone else get this impression?

For example, one of the most interesting parts of this reading was the brief section that discussed how the Chinese, Native American, and Japanese cultures view preservation. (p. 24-5) This portion really deserved to be expanded upon because the ideas presented were completely different, but just as valid as those presented in Historic Preservation. I wanted more detail into why these differing ideas are not a solution for contemporary America’s historical buildings.

I’m hoping that the chapters assigned next week will better detail how preservation connects with economic revitalization, gentrification, and similar issues.

Stray Observations:

-Loved the Eisenman’s Arrow thing. (p. 104)

-What is happening with the citations in this book? They are so few & far between.

Getting Hired and the Evils of Private Property

This week’s reading raised two questions for me; How do I get hired? and How important is private property in preservation?

My first concern is in the relevance of preservation to our qualifications. Last year, I attended a “Speed Dating” night of history professionals and history students. We were exposed to different avenues that our history degrees could lead us. One of those was historical preservation and it was one of the paths that I was most intrigued by at first. Unfortunately, my interest was way-laid as I learned from the two professionals that a MAHR does not really equate to historical preservation. Both of them had Master’s of Historical Preservation and either majored or minored in architecture.

As we learned from chapter 3 of Tyler’s Historic Preservation, knowledge in architectural history is a pretty essential component to being a historic preservationist (at least professionally). I would love to work for a city or in a State Historic Preservation Office, but I’m doubting my qualifications? Tyler asserts that preservation is done either by private individuals as part of a personal crusade, or government entities. My question is…how does one make a living in this? Who is doing these jobs and can we, as MAHR students, actually get hired?

I am also contemplating the tricky issue of private property. I was disappointed in the toothless National Register “Does and Does Not” list. While it’s wonderful that the register identifies places and “encourages their preservation”, I was dismayed that it has no power to protect or guarantee preservation. In true American fashion, the Register does not, “restrict the rights of private property owners in the use, development, or sale of privately owned historic property.” (p. 49) What then is the point? If we are not going to actually fight the good fight, why bother identifying those places at all? I was particularly irked by Tyler’s assertion that “it was politically necessary to leave such control (federal government protection) out of the original act.” (p. 50) I’m exposing my radicalism, but I believe that once artifacts and places mature past a certain point, they should enter into the public domain and should be removed from private ownership in order to be enjoyed by all. It is no different than classic literature.

I know. That will never happen. But I’d like to see preservation have a little more punch and power. Had we had that in Boise, we might not have lost so many fantastic historic buildings downtown to the gharish mall renovation in the 1970’s or seen so much gentrification and renconstruction of historic districts like the North End or Warm Springs.

Historic Preservation and Boise

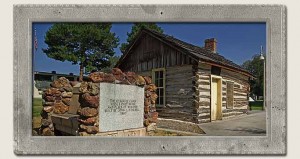

In Historic Preservation’s introduction, the authors’ talk of a movement from “quantitative to the qualitative” in order to “preserve our built heritage because it represents who we are as a people” (15). While recognizing this link between buildings, history and people, I would expound further that part of what makes a building aesthetically important is its symbolism. I am thinking of structures that to the eye are not necessarily grand or imposing, the O’Farrell Cabin or the Pierce Courthouse, but whose fundamental crudeness embody simplicity conjoined with the precariousness of survival in pioneer times, yet simultaneously they also symbolize the advent of Euro-American expansion, subjugation of the indigenous way of life and the exploitation of nature. Europe emptied its “excess” populations into America to observe the biblical injunction to be “fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” And by God we did so.

O’Farrell Cabin (Boise, built 1863)

Pierce Courthouse (Shoshone County, built 1862)

The text also gives an overview of two competing ur-theories of preservation. I understand the criticism of Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration methods that allowed for reconstruction with a lot of artistic license “not based on the original design,” but using what he esteemed appropriate, however I also like the creativity it allows (20). And while agreeing with Ruskin that there is grandeur, a sense of ancient nexus in untouched ruins, perhaps his vision is overly romantic in an unpractical fashion. As the text suggests there is a middle ground in this tension depending upon the building or structure, and the subjective taste of persons and period.

The explanation on page 81 was helpful to me in understanding why, sometime in my life, homes in Boise that had always been described as “Victorian,” suddenly at least to me, began to be described as “Queen Anne.” Apparently, there is little historical link to Queen Anne (R. 1702-14), but the term Victorian is reserved for “the period of Queen Victoria’s reign not a style.” Chastise yourself accordingly.

In Historic Preservation, the authors’ talk of buildings being “links between what came before and what will come in the future” reminding me of the stories in Letting Go? about the house on Hopkins Street and the Eastside Tenement Project (104). It also made me think of the Central Addition section of Boise if it is viewed “only in terms of its current condition,” which is dilapidated (104). As described in Preservation Idaho’s website, the Central Addition (bounded by Front, Myrtle, 2nd & 5th streets) was platted in 1890, was home to many of Boise’s early elite and only has buildings still standing through ‘preservation by neglect.’ When the railroad came to Boise and extended east in 1903, it was only a block from the neighborhood inducing those of means to move out. Illustrating that the wealthy still have options today that others did not, and do not have, a 2013 AP story on NBCNews.com reported that “minorities suffer most from industrial pollution” while the “poor, uneducated breathe the worst air.” Our text’s passage on teardown exactly mirrors the problem for the Central Addition where the land is valued far and above the value of the remaining houses (117). A January 20th, 2015 Idaho Statesman article states that part of the Central Additions is owned by a developer who has planning permission for a seven-story apartment block, with parking and commercial space valued at $24 million. According to the story, the developer and preservationist are on good terms and hope to move three houses built over a hundred years ago. The developer says he will give the houses, and pay to move them, to anyone with a viable plan for their preservation. Prompted by this week’s link in our syllabus, the houses concerned are shown below.

Jones House (built 1893) on 19 February 2015

Fowler House (built 1894) & Beck House (built 1906) on 19 February 2015

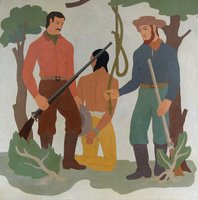

New Deal programs were responsible for many works in Idaho including what is now termed the Old Ada County Courthouse, a 1939 Public Works Administration Art Deco/ziggurat style building that boasts murals completed under the Works Progress Administration. The building’s future was in doubt until it was announced, in the February 9th, 2015 edition of the Idaho Statesman, that the building will become a University of Idaho Law and Justice Learning Center, in accordance with an agreement between the state and the University of Idaho. At least one of the WPA murals proved controversial when it was uncovered in 2008, because it depicted two white men preparing to hang an American Indian. Even the wording above can be contentious, are they preparing to hang or lynch the Native American? Hang may imply some sort of criminal offense, trial or justice (assuming such concepts were afforded to American Indians) whereas lynch conotes a starker reality.

WPA Mural in the Old Ada County Courthouse

Some wanted the mural painted over, as reported by Ann Finley writing in the Boise Weekly (30 July 2008) who quoted Larry McNeil, then and currently a BSU art professor, who said it should be painted over because of its offensive nature. Many Native Americans and others agreed with him, however Idaho’s five federally recognized Native American tribes, in accord with the State of Idaho, agreed to the mural’s continued presence in the courthouse conditioned upon an interpretative plaque which addressed “the bloody clashes between the cultures that occurred as white settlers took over the Boise Valley a century ago” (Betsy Russell, Spokesman-Review, December 12, 2008). The debate over this mural is instructive to all who are interested in how we should deal with artifacts, objects, and depictions of racism in our history. Should we hide them, ignore them, or destroy them in case they encourage further discrimination? Or is it we subconsciously want to erase them because they are reminders of a past that indicts our hallowed version of then, while also accusing us in the present? I believe the tribes and the state made the correct decision in keeping the mural rather than sparing our feelings by destroying a work that hurts today’s sensitivities.

I do believe planning review, design boards and historical preservation districts should be an integral part of any development or existing community. Though my proviso is that rules should be in place prior to anyone buying property and any proposed change after that needs to be evaluated in a manner sympathetic to property owners.

Viollet-le-Don’t Touch my Buildings

This is my first foray into Historic Preservation literature, and I’ll admit I was a little wary and had a few preconceived notions about how engaging this book would be or not be. I was pleasantly surprised and entirely engaged in the reading. The authors do a great job of introducing the history of preservation practices and legislation in the United States while intermixing the theoretical and philosophical background of different schools of preservation.

While studying archaeology both here and in the UK, I often encountered the question of “Why?” Why do we spend long, hard, cold days in the field minutely recording and recovering pieces of the long dead past? Why do we meticulously map and illustrate standing buildings? These are great essential questions of archaeology, history, and preservation – of public history in all forms. This book addresses these questions through the theoretical discussions of how preservation should and has occurred in the United States. The authors pose the question “Does preservation stand in the way of progress?” (p. 12). They answer this question using numerous sources, but my two favorite quotes sum up my feelings on the issue rather nicely. The first is from John Lawrence: “The basic purpose of preservation is not to arrest time, but to mediate sensitively with the forces of change. It is to understand the present as a product of the past and a modifier of the future.” (p. 14). The second, in the authors’ own words, supplements the first quotation and serves to begin answering the essential questions I mentioned earlier. “Our society will have matured when its primary focus shifts from the quantitative to the qualitative – when we recognize the need to preserve our built heritage because it represents who we are as a people.” (p. 15).

How then should we preserve the past? I absolutely loathe the philosophy of Viollet-le-Duc. Rebuilding structures as the ‘should have been’?! How pompous and narcissistic! However, this was certainly the philosophy in the United Kingdom during the Victorian period. It was practically championed by Queen Victoria herself and is exemplified in the current structure of Edinburgh Castle. It was basically redesigned under Queen Victoria’s orders to look more like an ancient fort. The problem is, now everything dates to the Victorian period except two buildings! On the other hand, leaving structures completely untouched is a rather melancholy thought. I am far more a fan of Ruskin and the idea that “The greatest glory of a building is not in its stones, or in its gold. Its glory is in its Age.” (p. 22). However, I believe both philosophies are cautionary tales that should be used as points to start the discussions of individual preservation projects. I also very much enjoyed the inclusion of preservation philosophies of other cultures. I was particularly intrigued by the Japanese philosophy that reflects the cycle of life, death, and renewal. The question for modern preservationists is how can elements of each philosophy serve to preserve this particular structure, in this particular setting?

The evolution of preservation movements in the United States was very interesting. It is easy to see connections between the changing theories in both preservation and history. Both switched from a focus on prominent men or their houses, to thematic research or preservation. In light of the piece we read about the Black Bottom, I appreciated the section “A Reaction Against Urban Renewal”. The authors poignantly point out the relationship these projects have with the communities in which they are implemented: “The past was no longer being ignored, but now was purposefully being destroyed.” (p. 44). The authors point to Jane Jacobs’ book The Death and Life of Great American Cities to further emphasize this point. “Her book was an important catalyst in stirring the public’s recognition that more than just saving some landmark structures, preservation dealt with preserving the very fabric of communities.

As a final thought, I appreciated the list of Boise’s endangered historic sites. I only knew where a few of them were and I am intrigued by those listings and by the bike tours mentioned by Mandy. And as a final, final thought – Does anyone else really dislike modern architecture or is that just me? Straight lines, no embellishment, harsh, cold materials. No thank you.

Good Job, Boise, on historic preservation!

Historic Preservation

2/22/15

Reflections on both Norman Tyler et. al Historic Preservation book and the 2010 “Endangered in Boise” blog for Preservation Nation (Timberline High School). This week’s readings were super interesting to me, and reminded me of the value of historic preservation law, at all levels, plus more so, the importance of community awareness about historic buildings as part of our cultural heritage.

Thanks to Mandy for mentioning Preservation Idaho’s bike ride tours. Have any of you taken a walk with Dr. Todd Shallat, or Barbara Perry Bauer of TAG History, Dan Everhart, or Mark Baltes in Boise neighborhoods? If not, go for it! What a great way to learn about Boise’s great architectural history, and the mistakes and successes of communities, architects, local design review, and more. The best tour I had was a Craftsman/Arts and Crafts/Bungalow walk with Shallat in Boise’s North End. I enjoyed the architectural styles part of this book, and realized there are so many great buildings/residences in Boise that are representative of these. Let’s hope they are preserved. Just like those great Chicago Tribune buildings, Frank Lloyd Wright homes, and cool bungalows. All in all, I think Boise has done an incredible job saving, restoring, reusing, and protecting our architectural heritage.

Next, here are a few places in Boise that have raised my ire:

-The Castle on Mobley Drive/Warm Springs Ave. (What happened to Historic District design review here? The text offers answers, but geez, come on…)

-The destruction of the Delamar boardinghouse and other buildings during Boise’s 70s urban renewal. Thank good ness it stopped short of the Egyptian, but we lost a lot of cultural heritage through the destruction of buildings.

-The “Hole” – now Zion’s Bank Building. Heritage, or moving forward? The only sign of the historic building history here today is the sign on 2nd floor. Hrrrumph? (And, the “Temple Spire” has ben altered – yes?)

-Teardowns – this is common in Seattle, Portland, and now, Boise. Latest new residence on Warm Springs is one example. Some old 50s home being leveled too . At what point do we lose the meaning of place and time? (See 103-105)

-The Foster’s Warehouse – lost that historic preservation fight. Another hrrrumph.

-What ever happened to the church that was being renovated for the TRICA Arts Center?

-Has the new Owyhee paid homage to its roots? What happened to the neat old photos of the 1910 building? At least it kept the high, decorated ceilings.

-Simplot home on 13th Street by 13th Street Grill – how long has that been in “historic preservation” progress? Can anyone talk to legal/NHPC mandates for these type projects?

-And another Simplot irk…JUMP. And to think the old beautiful train station once graced that area.

And here are a few places in Boise that have raised my curiosity, support, and respect:

-The Basque Museum & Cultural Center’s Cyrus Jacobs-Uberuaga Boarding House. Ntl Register of Historic Places, and the community archaeological dig that supported the SHPO’s work when building was undergoing restoration. Very cool.

-Russ Crawford’s untiring work to restore the Mode Lounge, sign and all…plus, his search for old architectural and business photos at the ISHS archives. Also, the similar work in the Alavita/Fork lounge areas, with historic photos and restored light fixtures.

-The renovation of the Modern Hotel – keep that Travel Lodge feel, and way to go with adaptive reuse, Linen District!

-Preservation Idaho’s “Onions and Orchids” annual awards.

-So many downtown buildings that are being used for businesses.

2010 Endangered in Boise. What a great thing that high school students are involved in historic preservation! I loved the blog. I was not familiar with all the items, but I think a few “won” and a few became extinct? Some of you worked on Central addition, yes? Out of the woods, or not? Block 44; still precarious, as are many of the Carley properties – what about revitalization just for the developer’s economic interests? 1000 Block – Alaska, etc…it’s too bad Boise State moved out of that and into the really sterile BoDo (“FroDo”) building. Progress is good, but heck, they could have stayed in two places. Speaking of BSU, the article spoke of the University Inn, which was torn down for the university’s most tech building yet, and a formal entrance to the university, and many of the quaint homes in the neighborhood near Broadway have been slashed and burned for bigger, taller Boise State buildings. Not as bad as the St. Luke’s takeover, though. Googie still stands, thankfully not a Sambo’s, and that whole area I predict will be the next renovation area for Boise, along with Garden City’s Chinden Blvd. Bring on more art, wine, beer and nurseries.

Other comments that resulted from the readings:

-City planning and historic preservation, adaptive reuse, etc…”brown and greyfield” areas. Boise is littered with these old, defunct strip mall areas, lots of asphalt, and propensity for damage, crime and worse. They are blights on the land. Some cities are now re-building these areas into combined work/play/living areas. Kind of like the old downtown buildings that are now apartment living complexes, which has “saved” a lot of our architectural beauty and history.

-LeDuc vs Ruskin: restoration of buildings “as they should have been?” or “As they are, in all glory of its age?” Interesting – would love to talk more about this.

-Other cultures: I was fascinated to learn of other cultural perspectives about physical structure: the Japanese life/death cycles and perpetual renewal of structures (tear down and rebuild); Chinese saving through art, images, and writing; and Native American thought that place is sacred, not structure (Mother Earth gives and reclaims). What do the Chinese in Boise think abut the removal of the Hop Sing, or the Chinese Laundry by Gernika, or other cultural sites?

-Really liked the Greenwich Village infill (compatible and contrasting elements)

Architectural Fun in Boise

If you have not done so already, I give you a challenge to participate in Preservation Idaho’s bike tour of architectural styles found in Boise. There are three reasons to do so: you get to ride your bike, you get to learn about Boise history, and the best reason of all, is that it is free. (Or at least has been). I have participated in two bike tours. The first was the Art Deco tour of the North End. My life centers on the Bench and so I was amazed about the large number of homes both large and small that contain elements of the Art Deco style. The second tour was about small houses on the Boise Bench created by an architect who cared nothing for architectural rules and regulations. He just put together elements that he liked of all types of architectural styles. (His name escapes me now which does not help with the point that I am trying to make about this being a memorable experience). These homes are largely located in the Rose Hill area. If you Google 4006 Rose Hill Street, you can see an image of his work. As you can imagine, these houses were the laughing stock of proper architecture. Now, they are seen as unique homes full of character.

So this brings me to the book. How can preservationists and new developers come to a consensus on what to preserve, what to build, and in what style? If Mr. No-name architect did not have the opportunity to build in his wonky way, would Boise now lack a distinct house style different from anywhere else in the U.S.? Preservationists, I think, have to have the ability to see value in the past as well as what will be valued history in the future. Also, the preservationist has to see value in architecture (or sites, etc.) for themselves, but for other groups within the community. There is a great responsibility to preserve the collective history. The book mentions later that even though for me, personally, Starbucks is not especially important. But, in how many years will generations younger than I want to preserve the coffee shops as they are today as a representation of the culture of the 2000’s?

Then again, there are the hard questions. At what point do old buildings need to be demolished? Even if I find a building to be too far gone, but it the cultural center for others, who gets the say? Or should get the say? Also, if we look too much to the past, are we limiting future good things?

Hard philosophical questions aside, take a bike tour next time the opportunity arises.