As I noted in my previous posts regarding Historic Preservation, I do have some concerns with the broadening definitions of what historically important and about what constitutes “taking.” However, I do not intend to rehash my concerns here. I found the second half of Historic Preservation to be full of useful content on the legal and technical aspects of historic preservation. I appreciated the information about conservation and the four types of intervention, (preservation, restoration, reconstruction, and rehabilitation) and found the text to be an illuminating and thorough-going treatment of these subjects. Conservators in the field have done remarkable research and provided guidelines and solutions for each type of intervention. The Secretary of the Interior standards frequently referred to in the text appeared to be pretty thorough and reviewing the standards on the National Park Service website confirmed that fact.

While I have little interest in being a conservator, I was intrigued by

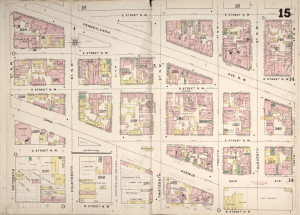

all that was contained in the “Research and Documentation of Historic Properties” section of Historic Preservation. I love the description, “Researching historic properties is both a craft and art. The craft is in piecing together information on a property from disparate sources; the art is in its interpretation.”[1] I believe that researching the history of a building or district sounds fascinating.

In exploring the National Park Service website I decided to look at two obscure Civil War-era battles, the Bear Creek Massacre in Franklin County, Idaho and the Battle of Ball’s Bluff in Virginia. The first was listed by the Civil War Advisory Commission as a site worthy of protection in 1990. Beyond some limited use of the site for interpretation by Shoshone tribal members and a wayside signs, little has been done beyond at the site. That is why I found the Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields, Far Western Battlefields: States of Colorado, Idaho, and New Mexico of particular interest. The “Update”, published in 2010, provided a lot of information about what has or has not been done relative to the site, as well as what steps need to be taken to further protect the site.

Ball’s Bluff a relatively well-developed park, but is a little less impressive with regard to NPS provided information. The only readily available NPS document was a one page report by the Civil War Sites Advisory Committee. This dearth of information is offset by a wealth of information provided by other sources, in particular NOVA Parks, an inter-jurisdictional organization in Northern Virgina.

[1] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel and Ilene R. Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice, (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009), 202.