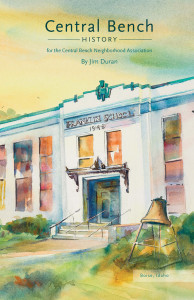

The Idaho Black History Museum may seem a bit out of place in Idaho seeing as the population is only .8% Black. (Census) This museum is located in downtown Boise right next to the Boise Art Museum, the Idaho State Historical Museum, and the Boise Zoo. The museum which is housed in the historic St. Paul Baptist Church is in prime real estate in Boise which was more than likely a strategical move by the museum founders. On the surface, Idaho’s past doesn’t seem to have a rich African American story, but this museum proves otherwise. According to the website, the museum exists to “build bridges between cultures to explore issues that affect Americans of all cultures and ethnicity.” (IBHM.org About Us)

According to Dr. Jill Gill, former Board Member of the museum and history professor at Boise State University, it is a volunteer based museum. The IBHM has no paid professional staff. “Therefore, the board runs the museum. It creates the exhibits, and brings in traveling exhibits, solicits donors, rents the facility to other groups, manages the site, sells items for fund raising, and arranges for volunteers to open the museum for business.” Due to the volunteer-run system, the exhibits are mainly put together by amateurs without any formal curator training. This gives the museum a different feel than other museums in the surrounding area.

Just by walking into the museum, you can tell that it truly is a passion project by members of the community. Gill who has served on the board for many years has helped with events and spoken at some. She has worked on fundraisers, created exhibits, and even helped clean up the museum. Being a board member and volunteer means helping out with everything and truly being involved in every aspect of the museum. You can tell by the exhibits that there is a large amount of input and help from the community. The volunteers that are at the museum regularly give great direction and are extremely helpful. Last time I visited the museum, I only got to look at a couple of the exhibits because I was wrapped up in a great and informative conversation with one of the volunteers (who happened to be the grandson of the man who built the church). This all gives the museum a homegrown, comfortable feeling.

Gill spoke about the size of the museum and their goals that include expanding the donor and revenue base so they can hire part-time professional help. They also hope to bring in new traveling exhibits. They hope to gain more volunteers and to expand its outreach further across the state. “The IBHM has always supported human rights and been part of the Idaho human rights movement, which it will continue to do so via its educational mission.”

Gill describes how her interest in Black history led her to get involved with the museum back in 2002. She explained how the Boise State University history department has had a history of representation on the board and have “tried to be helpful in connecting university classes/programs/resources with the museum and vice versa.” Gill describes the success of the museum as simply the number of viewers as well as engagement of the audience. “Oftentimes classes of school kids come through, and success would be measured by indicators that visitors have learned something, or though of things in a new way as a result of the exhibits/programs.”

Visitors can currently visit the museum and see the large piece of artwork by Pablo Rodriguez depicting the journey of Black Americans throughout history called Slave to President.