I originally met Mr. Reeves through an oral history class taught at the Nampa Public Library in February 2016, courtesy of the Idaho Humanities Council. The two-hour class introduced us to the work of an oral historian and was a wonderful starting point for those interested in oral history either as a hobby or a profession.

To begin it is worth noting some of Mr. Reeves’ bona fides. The following information is drawn from the University of Wisconsin-Madison staff directory. Mr. Reeves manages collecting and curating oral history recordings, as well as communicating and collaborating with interested individuals about the art and science of oral history in both Wisconsin and Idaho. He is responsible for twenty oral history projects in both states covering such topics as cultural, political, and environmental history. He has been published in such journals as the Western Historical Quarterly, the Public Historian and the Oral History Review. He is also the managing editor of the Oral History Review overseeing day-to-day operations, including its social media initiative. He also works with the editorial team to add multimedia (both audio and audio/visual) content into the journal’s articles. Finally, Reeves has held various leadership roles in the national Oral History Association.

Mr. Reeves near twenty-year career began with a part-time, six-month project for the City of Boise in 1997. From 1999 until 2007 he served as Idaho State Oral Historian, Idaho State Historical Society (ISHS). He left that position to become the head of the oral history program at the General Library System at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, which encompasses forty libraries on campus.

Mr. Reeves’ educational path typifies oral historians. He received a Bachelor of Arts, History from Idaho State University and a Masters of Arts, History from Utah State University. In both programs he selected projects that allowed him to do oral interviews in conjunction with other research he was conducting. Reeves stated that the few full-time jobs in oral history require at least a master’s degree, typically in history, folklore, library sciences, or journalism. Recently Columbia University began offering an Oral History Master of Arts.

Interpersonal skills are of paramount importance, being a good if not a great listener. He quoted a friend, Sarah White, who says, “Being a good listener requires not only the ear, but the brain and sometimes the heart.” Being a good researcher is essential so you know the person or people you are interviewing and the topic being discussed. Finally, perseverance is vital. People will back out of interviews leaving you stranded. Finding funds for different projects is frustrating. Knowing you have a good idea and the interest in the topic is not enough, it takes perseverance to get the project done.

When asked about salary, Mr. Reeves chuckled and said, “In the humanities there is never a poverty of ideas, only a poverty of everything else.” As the State Historian for the Idaho State Historical Society his starting wage was $13.50. No oral historian positions were found on National Council of Public History jobs board, however other entry level jobs on the site started at $15-$19.

“Oral history is what I do and who I am,” said Reeves. His position is funded by the library to promote oral history on the campus, especially focusing on capturing the history of the university. His projects fall into two “buckets,” campus life stories and project or topic-based oral histories. As an example of the first he cited a recent interview conducted with a wildlife biologist who talked about his work and the history of the university over the last nearly forty years. Reeves would like to do more such interviews, but as a one-person operation he typically can only do a few each year.

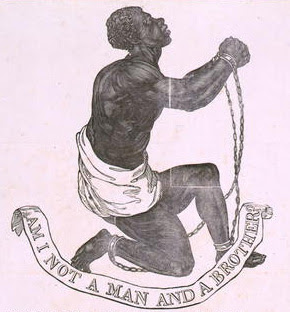

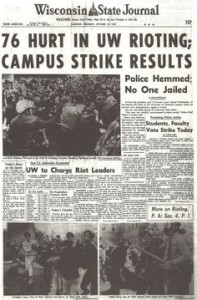

A project or topic-based project can be found in the interviews he is conducting around the 2011 protests which occurred at the state capital and on campus regarding changes Governor Scott Walker and the Wisconsin legislature were trying to implement. Since summer of 2011 he has been interviewing graduate students and some faculty and staff who were deeply involved in those protests. Another hot period for protests on campus occurred between October 1967, when there was an anti-war riot on campus, and August 1970 when there was a bombing on campus. These interviews continue with people who were actually on campus at that time.

Mr. Reeves also does off-campus work for the Wisconsin State Historical Society. He does training and workshops for them around Wisconsin, at their annual meeting and out of state such as the one in Nampa. He also works with different people who aren’t paid historians but who do oral history work ancillary to their jobs. Finally, he works closely with the full-time oral historian archivist at the vets’ museum. All of this exemplifies the campus ethos to get outside of campus and help others.

“Oral History Now and Tomorrow” was the topic of a panel discussion at the 50th Anniversary conference of the Oral History Association. Some current issues are:

- Now that you can put digital audio online, should you? What are the ethics of doing so?

- In an organization that prides itself on being egalitarian, who gets left out when there is a focus on degrees and professional development?

- Oral history in crisis or contemporary settings, when is it okay to start doing oral histories?

- Are there differences in the way a feminist may conduct an oral history project as opposed to someone not imbued with feminist history or feminist studies.

The oral historian techniques and methodologies should be in every historians’ toolkit. Hearing and not just reading the words of those who witness history provides a bonus of information that may be otherwise missed by any student of history.