“Embedded with the reenactors” stirred some strong feelings for me. As I’ve said before, I love Old Fort Niagra. Reading Kolwalczyk’s description took me back. Which is why I think reenacting is popular with certain people, a yearning for something that might be missing in their lives at that moment. That’s not to say that everyone who reenacts is missing something in their lives, but the way the “hobby” is portrayed, that’s what it looks like from over here.

Regarding wearing Confederate grey, I think less people wear it these days because no one wants to play on the loosing team. But all joking aside, that article illustrated some of the reasons reenacting is popular with an older whiter crowd. They came of age in the ’60s, when there were three television channels, and nothing much else to do besides play outside. And what better to do than rehash the days of “Cowboys and Indians”, or the Rough Riders up San Juan hill, or Pickett’s charge.

But to me, reenacting, as it is presented in Kolwalczyk’s article, is worshiping at the altar of toxic masculinity. Having just read Kolwalczyk’s piece that Ann Little recommends, I think he might believe it too. And perhaps that’s why there aren’t reenactments of suffragettes. And maybe the wounds are still too fresh to have reenactments of the civil rights struggle, especially in the wake of current “situations”. Reenactments “thumb their noses” at the losers, which is why French-Canadians try to disrupt the reenactment of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, and Northern Irish Catholics get so incensed when Northern Irish Protestants march through their neighborhoods on the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne.

With regards to Wikipedia, I have no words. It is an online encyclopedia, and given the way it is set up there has to be some kind of regulation. But credentials should count for something.

Category: Uncategorized

History Done by Non-historians

These articles bring up some good points on how to think about history done from non-historians. Where do we draw the line on scholarly authority? Are sound resources the key in the debate? I feel like I change my mind on that subject weekly and do not ever have a concrete opinion on the matter.

With reenacting, I appreciate that on any one battlefield you can have casual enthusiasts who are just there to have fun mixed in with the hard-cores who are particularly proud of their authenticity and dedication. As brought up in “The Limited (and Queer?) Vision of American Historical Reenacting”, much of this reenacting is done by older, white men romanticizing the past. It makes me wonder how many men don their reenactor roles to “escape” into a hyper-masculine world against a changing society that may seem “threatening” to them. I’m sure many are passionate about history, but to some maybe only in a way that maintains white patriarchy. The few articles referencing reenacting made me think of the book that some of us read last semester titled Confederates in the Attic, which addressed the undying nature of the “War of Northern Aggression” to Southerners. To many, reenacting connected them to their heritage and a simpler, better time. The Civil War refuses to die because the war is still so personal. This book was published in 1998, so I’m wondering if between 1998 and 2012, perhaps the Civil War mania began to lessen as “Why Doesn’t Anyone Think It’s Cool to Dress up like a Confederate Soldier Anymore?” suggests with dwindling attendance at Sons of Confederate Veterans events.

Another side note on “The Limited (and Queer?) Vision of American Historical Reenacting”, a remark was made that maybe in the future we will see women and minorities reenact struggles and confrontations in the future. This comment reminded me of people who had dressed up to participate in the Women’s March in January. Particularly, I thought of a few women I saw dressed up at Victorian Suffragettes. I do not know if those women would consider themselves reenactors, but I thought it was a step in the direction that the articles was talking about, and an example of connecting yourself to history to prove a point.

Regarding Wikipedia, all of the information was new to me, feeding into the statistic that women are not as active contributing as men. Since I have never tried to edit an article, I did not know the content and source guidelines. It does make me feel better about getting quick facts and an overview since there are guidelines in place to deter internet trolls, but I can understand Messer-Kruse’s frustrations. Being an expert in your field and then told that you do not have the right kind of sources to edit a Wikipedia article would drive anyone crazy.

enticing people to keep history

Although I am aware that historical preservation costs money, I found that much of second half of the book was an attempt to give historians a financial argument as to why it could behoove someone. That being said, I find it ridiculous that people not only want, but actually expect a financial gain as a reason not to destroy historical buildings. Even my favorite part of the second half of the book, Revitalizing Downtown, felt littered with facts like “The Main Street Center recently tabulated that the program led to the rehabilitation of 60,000 buildings (instant happy thought for me, over 174,000 jobs, and to $35 for every $1 spent.” (174) Why do we still look at our collective history in dollars and cents rather than with just sense?

Page 201 clearly shows a list of an entire budget of a project, including tax benefits of doing such a rehab. To me, if you don’t want to live in a historic district ( or own a business in one), then by all means do not. If you do, I feel it ridiculous that it takes an entire spreadsheet of cost accounting to help someone determine…. what exactly? Whether or not or history has value?

The other thought that consistently came up for me was that, what about areas that are historic to a certain group of people but are overlooked by others? With the idea of a commission in charge of what is historical and what is not, what about places like Garden City, known for its beautiful gardens…. that were built and maintained by the Chinese who, as second class citizens of their time, have conveniently been written out of that narrative? Those that have power are the only ones that seemingly can tell us what has history and what does not. Only fairly recently has history started to put into the narrative the significance of many race, class, and gender in the building of America. With this in mind I would hate to lose the history of these other disenfranchised groups simply because they were disenfranchised.

Part II is Worth Reading

As I noted in my previous posts regarding Historic Preservation, I do have some concerns with the broadening definitions of what historically important and about what constitutes “taking.” However, I do not intend to rehash my concerns here. I found the second half of Historic Preservation to be full of useful content on the legal and technical aspects of historic preservation. I appreciated the information about conservation and the four types of intervention, (preservation, restoration, reconstruction, and rehabilitation) and found the text to be an illuminating and thorough-going treatment of these subjects. Conservators in the field have done remarkable research and provided guidelines and solutions for each type of intervention. The Secretary of the Interior standards frequently referred to in the text appeared to be pretty thorough and reviewing the standards on the National Park Service website confirmed that fact.

While I have little interest in being a conservator, I was intrigued by

all that was contained in the “Research and Documentation of Historic Properties” section of Historic Preservation. I love the description, “Researching historic properties is both a craft and art. The craft is in piecing together information on a property from disparate sources; the art is in its interpretation.”[1] I believe that researching the history of a building or district sounds fascinating.

In exploring the National Park Service website I decided to look at two obscure Civil War-era battles, the Bear Creek Massacre in Franklin County, Idaho and the Battle of Ball’s Bluff in Virginia. The first was listed by the Civil War Advisory Commission as a site worthy of protection in 1990. Beyond some limited use of the site for interpretation by Shoshone tribal members and a wayside signs, little has been done beyond at the site. That is why I found the Update to the Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Report on the Nation’s Civil War Battlefields, Far Western Battlefields: States of Colorado, Idaho, and New Mexico of particular interest. The “Update”, published in 2010, provided a lot of information about what has or has not been done relative to the site, as well as what steps need to be taken to further protect the site.

Ball’s Bluff a relatively well-developed park, but is a little less impressive with regard to NPS provided information. The only readily available NPS document was a one page report by the Civil War Sites Advisory Committee. This dearth of information is offset by a wealth of information provided by other sources, in particular NOVA Parks, an inter-jurisdictional organization in Northern Virgina.

[1] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel and Ilene R. Tyler, Historic Preservation: An Introduction to Its History, Principles, and Practice, (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2009), 202.

Historic Preservation Part 2

I found the reading in Historic Preservation Part 2 to be enlightening and educational, especially in regards to laws and legal cases that have dealt with historic preservation. The discussion between preserving historical information and architecture focuses on the “historic significance,” a term “used to describe a property’s relative importance . . .” (Tyler, Ligibel, Tyler, 135).

Much of Part two deals with the legalities surrounding preservation and begins by saying, “The legal framework for historic preservation is largely based on land use law, with the traditional premise that property owners should have the right to do as they wish with their property.” (121) One significant case in 1926, Euclid v. Ambler Realty Company decided in favor of protective zoning and “overrides the interests of individual property owners,” which changed the tone for future preservation decisions and a change in the way of thinking. Other court cases have decided whether or not land should be preserved for future historic value, such as the decision of Penn Central. It is considered to be historic preservation’s “most important legal precedent.” It was decided in 1978 and it prevented a monstrous 55 story addition to the iconic landmark, Grand Central Station in New York city. This decision by the U.S. Supreme Court made guidelines for how historic sites are preserved and gave legitimacy to cities and governments that preservation is a “governmental goal.” (126)

Historic significance is the term best used throughout part two, as it provides the value of the conservative nature of the remaining book chapters. “A structure’s significance is based on two primary factors: historical or cultural importance and architectural value.” (135) Categorizing these factors about a site’s importance can help us evaluate in terms of historic value and, most important, the integrity . Part of the evaluation, according to the National Registry, involves these seven factors: “Location, Design, Setting, Materials, Workmanship, Feeling and Association.” (138) Certainly in evaluating historical significance, there are so many aspects that can contribute to a site and certain aspects can either add or detract from the evaluation. If a home is original, for example, or if it has undergone remodeling that is not true to its history. Events like relocation of a home can be a negative because the setting may have been of importance and, the prominence of the family that built the home or lived in it for a significant time can be a factor. Certainly the architect is an important factor and age, with a “commonly accepted, and government-supported, criterion for historic significance is . . . at least fifty years old.” (140) As a historian, one of the most interesting categories is National Historic Landmarks, which are a “special category of designed historic structures and properties with exceptional value or quality.” (150) These are places that are of importance to all Americans and one of the most famous is Graceland, the home of Elvis Presley, and also includes Mount Vernon, Pearl Harbor and Alcatraz Island.

The establishment of historic districts is very important in preserving the history and character of certain parts of cities and towns. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 gave governments the “power to create regulatory historic districts.” (155) It provided for the protection of properties of historic value but it also serves as a protection for the wrecking ball of redevelopment. It promotes people preserving wonderful homes and buildings and helps to improve property values for entire areas, oftentimes inner city locations. For example, I live near the historic district of the North End in Boise and enjoy the architecture of historic homes and businesses. Buildings downtown such as the fire station on 6th street built in 1902 now houses a nice restaurant after serving the people of Boise. Member of the Idaho Historical Society cleans the bell inside the building weekly. It is because of the dedication of people like them that many of Boise’s historical buildings remain for us to see.

Preservation 2

The chapter on legal basis for preservation made me frustrated, but not surprised, on the amount of red tape and legal precedence the government uses to allow or thwart owners’ rights to preserving historical buildings. The political and legal fighting between parties on historical significance is no different than when they argue laws or legislation. It should be called negotiations instead of litigations. Imminent Domain has been used, not just in cases of historic preservation, but also when it comes to expanding any kind of cities public works, like roads, landfills, and interstates. One thing is for certain the government will always change their minds and make it extremely difficult for an owner of a historic property to maintain it, make changes, or demolish it.

I thoroughly enjoyed chapter seven because this is what interests me about the preservation process. I see the issues with preservation and technology because with so many involved this could slow a process down. I liked how the chapter broke down the definitions of each term and idea one by one to explain it. The amount of different expertise needed to do each particular job is amazing. With the increase in older buildings being preserved I wonder if it would be easier for teams to be designated in areas with large historic districts, specifically in the east coast, where large areas can be designated to specific teams for preservations. The teams would have specific individuals with knowledge of the architecture to lead breaking the teams down by skill levels to maintain multiple structures. Similar to how the military combines multiple specialties or jobs skills to nation build or provide security I think the same idea could apply to preservation in large areas. Obviously, the major problem with this is going to be money and convincing the government to spend it. The idea seems sound and would allow for on the job training with apprentices and students.

The sustainability of the historic sites seems possible depending on the community’s involvement. Getting people to volunteer is easy, in my experience, because most people will want to in the beginning. The problem is not overworking the people and getting others to volunteer. Problems arise when trying to train and sustain the relationships with the government and communities on how to sustain historic projects for the future. Working around schedules and getting a life cycle schedule passed to maintain and sustain the historic building can be an ominous task if multiple agencies are involved and laws keep changing.

Preservation Gone Wrong

I know our reading this week dealt mostly with buildings and environmental sites but I was reminded of this botched fresco restoration that I’m sure all of us recognize from a few years ago.

Here is the link to an article showing how they made the most out a terrible situation. I thought you might enjoy it.

https://news.artnet.com/art-world/botched-restoration-of-jesus-fresco-miraculously-saves-spanish-town-197057

At What Cost?

On the back cover of Historic Preservation, the authors’ state, “It is an ideal introduction to the field [preservation] for students, historians, preservationists, property owners, local officials, and community leaders.” I agree, I found it a thorough introduction which answered many questions, often ones I didn’t know I had. I was interested to read how various groups, communities and governmental bodies created and used all manner of laws to achieve their goals. While I am not sure preservation is the area I want to work in, I will keep this book as a reference, just in case.

While I generally applaud preservationists’ efforts, and love much of what has been preserved, I am concerned about the increasingly broad definitions of what is historically important. The broader definition, the less historically important the project seems. In particular, I found that “Heritage Areas” and “Heritage Corridors” stretched credulity. To paraphrase the authors, are Heritage Areas now preferable to National Parks or National Monuments? I have to ask if economic factors are driving this movement. By this I mean that tourism, tourism-related development and the ability to retain more local control on the appearance, function and activities seem to provide self-interested, economic motivation for applying for this status. I think developing coalitions is useful and I would not want to discourage such efforts, but many of these projects seem questionable.

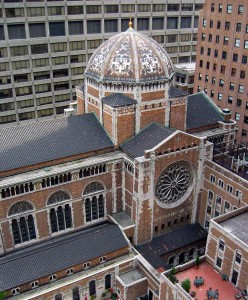

From a legal perspective, I think of St. Bartholomew Church in New York is an example of another problem. In disallowing their proposal to build a commercial tower as a way to generate income, the courts ruled that since the church was still able to function as a church and it could still perform its various missions if it sold off some of its stock portfolio, this was not a “taking.” The property owner was not trying to destroy this historic building but they are not given any latitude on how to raise funds and instead are forced to expend resources against their will. Must they maintain this historic property until their resources are gone? Once the parish has emptied their bank account, does it become the responsibility of the Episcopal Diocese of New York to maintain the property? I note this because I am aware of historic churches from various faith communities facing similar demands. What recourse do they have?

Historical Preservation Part 1

I found the reading of Norman Tyler’s Historical Preservation to be enjoyable and educational, as it speaks about the interesting historical sites, and how many organizations have been set up to keep these places intact from construction and/or demolition. With people becoming more aware and participatory in historic preservation during the past century, the importance of buildings and a building’s historical contribution has come to the forefront of society. “Preservationists need to recognize that the preservation of historic buildings should include not only the physical structure but also the history of the place.” (Tyler, 15). According to one passage that I read in Historical Preservation, the practice of “Historic preservation should be seen as more than the protection of older buildings.” The end result in preservation is to preserve buildings not as “inanimate structures . . .”. (15-16) Therefore, some buildings become seen as obsolete in the business of construction and development, but it does not mean that historic buildings and items are seen as worthless. Another aspect to be aware of is the practice of “facadism,” which only preserves the front or the facade of a building. With the bulk of the building destroyed, any historical significance of the building itself is lost. There are many lessons and facts of interest that ancient buildings and artifacts can teach, such as museums that store historic items, or preservation offices that study old documents and building sites.

Besides preserving artifacts and historic sites, many people have begun experimenting with different technologies, in an attempt to educate the public, as described by Tyler’s passage from Historic Preservation, “Some exhibits have blurred the line between education and entertainment, leading to a new term, ‘edutainment,’ which combines the two into one presentation.” (16) This form of entertainment can be both useful to amuse and excite, as well as educate individuals on different academic subjects. A perfect example that Tyler describes is the use of animation technology at Disney World’s Hall of Presidents. Holograph technology is another example of these types of exhibits and “edutainment.” Certainly new technologies and various methods will continue to help historians to not only preserve but to exhibit and share information in the future.

In Chapter two, Tyler describes the two distinct paths that preservation has taken since its earliest beginnings. He notes that “Private-sector activities tended to revolve around important historical figures and associated landmark structures, whereas government [preserves] natural features and [establishes] national parks.” (27) The National Trust brought those two paths together with the establishment of the Trust in 1949. In choosing sites for preservation, the Trust has been very selective over the years, with only “twenty-nine historic sites of exceptional significance that it administers completely.” (43) The Woodlawn Plantation in Virginia was the first site taken on by the National Trust. Other buildings are the Gothic Revival mansion in Tarrytown, New York and the Lower East Side Tenement Museum in New York City. The Trust also commits its resources to lobbying efforts in Congress as well as “publicizes its Endangered Properties List . . .” (44). The federal government’s push for economic stimulation following the two world wars provided yet another challenge to preservation. Urban renewal programs literally left many cities with blocks of emptiness having had many historic buildings demolished to make way for new. After the publication of Jane Jacobs’ influential book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, and the involvement of the National Historic Trust, the National Historic Preservation Act was passed in 1966, which helped with funding and listing of historical places in the United States and allowed for the development of historic district within our cities. State Historic Preservation Offices (SHPOs) as well as Section 106 procedures now help to protect historical properties. Thanks to the efforts of preservationists, buildings of such immense historic significance as Independence Hall have been saved for future generations.

Preservation

Americans had and still have a hard time to keeping historic houses due to urban renewal. “The Housing Act of 1949 and Urban Renewal Act of 1954 were meant to provide such a stimulus by making available federal funds to purchase and clear deteriorated urban neighborhoods.”[1] The federal government at this time felt that the first step to updating a dilapidated area was to tear it down. The government did not realize the historical significance of the buildings. The state and federal government felt that in order to improve an area they had to demolish dilapidated areas. The federal government called these places “blighted” areas. Old was not good therefor needed to be demolished. “The goal of urban renewal funding was to encourage investors to purchase the cleared sites at low cost and launch redevelopment projects.”[2] Destroying history of a certain area takes away from the overall embodiment of the community. The historical value and history of the community and how it developed is eliminated.

Historic preservation allows for the future of a community to understand how their town and city formed from diversity and immigrants. It is an actualization of the American dream being shown through community and historical involvement. “The National Trust, inspired by its English namesake, was created with the purpose of linking preservation efforts of the NPS and the federal government with activities of the private sector.”[3] It does not matter whether it is post-modern or colonialism type houses or property they need to be protected. The communities should see this as a high priority. The only obstacles I see in preservation of historic places and areas is federal funding. The other issue is whether the community finds it worth saving and historically significant. So many groups and federal regulations to work through also causes issues on whether a site become historic or not. The Federal government does not live in the areas or know the historical significances of places in small or medium sized towns. So, judgement made could be against the saving of historical local sites due to minor populations. Ghost towns, mining towns, and other minor places seem insignificant, but could be a major point of pride and significance to local communities.

[1] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel, and Ilene R. Tyler. Historic preservation: An introduction to its history, principles, and practice. WW Norton & Company, 2009. Pg. 44.

[2] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel, and Ilene R. Tyler. Historic preservation: An introduction to its history, principles, and practice. WW Norton & Company, 2009. Pg. 44.

[3] Norman Tyler, Ted J. Ligibel, and Ilene R. Tyler. Historic preservation: An introduction to its history, principles, and practice. WW Norton & Company, 2009. Pg. 42.