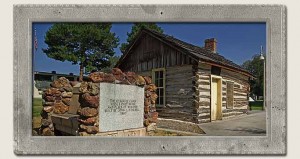

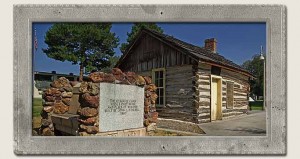

In Historic Preservation’s introduction, the authors’ talk of a movement from “quantitative to the qualitative” in order to “preserve our built heritage because it represents who we are as a people” (15). While recognizing this link between buildings, history and people, I would expound further that part of what makes a building aesthetically important is its symbolism. I am thinking of structures that to the eye are not necessarily grand or imposing, the O’Farrell Cabin or the Pierce Courthouse, but whose fundamental crudeness embody simplicity conjoined with the precariousness of survival in pioneer times, yet simultaneously they also symbolize the advent of Euro-American expansion, subjugation of the indigenous way of life and the exploitation of nature. Europe emptied its “excess” populations into America to observe the biblical injunction to be “fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth, and subdue it: and have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the fowl of the air, and over every living thing that moveth upon the earth.” And by God we did so.

O’Farrell Cabin (Boise, built 1863)

Pierce Courthouse (Shoshone County, built 1862)

The text also gives an overview of two competing ur-theories of preservation. I understand the criticism of Viollet-le-Duc’s restoration methods that allowed for reconstruction with a lot of artistic license “not based on the original design,” but using what he esteemed appropriate, however I also like the creativity it allows (20). And while agreeing with Ruskin that there is grandeur, a sense of ancient nexus in untouched ruins, perhaps his vision is overly romantic in an unpractical fashion. As the text suggests there is a middle ground in this tension depending upon the building or structure, and the subjective taste of persons and period.

The explanation on page 81 was helpful to me in understanding why, sometime in my life, homes in Boise that had always been described as “Victorian,” suddenly at least to me, began to be described as “Queen Anne.” Apparently, there is little historical link to Queen Anne (R. 1702-14), but the term Victorian is reserved for “the period of Queen Victoria’s reign not a style.” Chastise yourself accordingly.

In Historic Preservation, the authors’ talk of buildings being “links between what came before and what will come in the future” reminding me of the stories in Letting Go? about the house on Hopkins Street and the Eastside Tenement Project (104). It also made me think of the Central Addition section of Boise if it is viewed “only in terms of its current condition,” which is dilapidated (104). As described in Preservation Idaho’s website, the Central Addition (bounded by Front, Myrtle, 2nd & 5th streets) was platted in 1890, was home to many of Boise’s early elite and only has buildings still standing through ‘preservation by neglect.’ When the railroad came to Boise and extended east in 1903, it was only a block from the neighborhood inducing those of means to move out. Illustrating that the wealthy still have options today that others did not, and do not have, a 2013 AP story on NBCNews.com reported that “minorities suffer most from industrial pollution” while the “poor, uneducated breathe the worst air.” Our text’s passage on teardown exactly mirrors the problem for the Central Addition where the land is valued far and above the value of the remaining houses (117). A January 20th, 2015 Idaho Statesman article states that part of the Central Additions is owned by a developer who has planning permission for a seven-story apartment block, with parking and commercial space valued at $24 million. According to the story, the developer and preservationist are on good terms and hope to move three houses built over a hundred years ago. The developer says he will give the houses, and pay to move them, to anyone with a viable plan for their preservation. Prompted by this week’s link in our syllabus, the houses concerned are shown below.

Jones House (built 1893) on 19 February 2015

Fowler House (built 1894) & Beck House (built 1906) on 19 February 2015

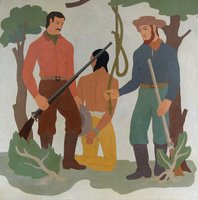

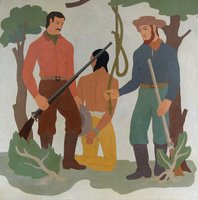

New Deal programs were responsible for many works in Idaho including what is now termed the Old Ada County Courthouse, a 1939 Public Works Administration Art Deco/ziggurat style building that boasts murals completed under the Works Progress Administration. The building’s future was in doubt until it was announced, in the February 9th, 2015 edition of the Idaho Statesman, that the building will become a University of Idaho Law and Justice Learning Center, in accordance with an agreement between the state and the University of Idaho. At least one of the WPA murals proved controversial when it was uncovered in 2008, because it depicted two white men preparing to hang an American Indian. Even the wording above can be contentious, are they preparing to hang or lynch the Native American? Hang may imply some sort of criminal offense, trial or justice (assuming such concepts were afforded to American Indians) whereas lynch conotes a starker reality.

WPA Mural in the Old Ada County Courthouse

Some wanted the mural painted over, as reported by Ann Finley writing in the Boise Weekly (30 July 2008) who quoted Larry McNeil, then and currently a BSU art professor, who said it should be painted over because of its offensive nature. Many Native Americans and others agreed with him, however Idaho’s five federally recognized Native American tribes, in accord with the State of Idaho, agreed to the mural’s continued presence in the courthouse conditioned upon an interpretative plaque which addressed “the bloody clashes between the cultures that occurred as white settlers took over the Boise Valley a century ago” (Betsy Russell, Spokesman-Review, December 12, 2008). The debate over this mural is instructive to all who are interested in how we should deal with artifacts, objects, and depictions of racism in our history. Should we hide them, ignore them, or destroy them in case they encourage further discrimination? Or is it we subconsciously want to erase them because they are reminders of a past that indicts our hallowed version of then, while also accusing us in the present? I believe the tribes and the state made the correct decision in keeping the mural rather than sparing our feelings by destroying a work that hurts today’s sensitivities.

I do believe planning review, design boards and historical preservation districts should be an integral part of any development or existing community. Though my proviso is that rules should be in place prior to anyone buying property and any proposed change after that needs to be evaluated in a manner sympathetic to property owners.