The fundamental crux of the conundrum King outlines, is that those who are hired to perform environmental impact work and cultural resource reviews, have a self-interest in conforming as much as possible to their employers’ vision. A company or contractor is being paid to, ostensible, independently evaluate a proposed project to see if it conforms to the law. The business who has proposed the project is paying another business to evaluate its project. This system incentivizes cronyism of a sort, or what others may call good business practice or even plain old common sense. In this situation, how can a company “possibly do a responsible, even semi-objective job of analyzing its impact?” (34). As the old saws go, he who pays the piper calls the tune, and don’t bite the hand that feeds you. Throughout our history, humankind has proved that the promise of lucre will often override the best intentions or the noblest aims. So how do you put the incentive on the other side, on the side of an honest impartial environmental review? An obvious answer is to have the government perform the review, or be the one, who does the contracting, and bill the project proposer, or have the proposer pay for the evaluation up-front. This way the government would choose the contractor and be the contractor’s employer, in contrast to the situation King describes. Admittedly, the likelihood of such a system coming to fruition is an era of hostility to “big government” is unlikely. Certainly one could poke many holes in this proposal, such as it could succumb to corruption and abuse through outright malfeasance, or through the revolving door from government regulator to working for those formerly overseen, but it seems that anything is better than the current situation.

The second major issue that King raises is lax enforcement by government agencies that seem to check boxes rather than complying with the spirit and intent of the law. In one case of blatant bias we are told that “agency advocacy of projects whose impacts they are supposed to analyze objectively is usually more subtly expressed than this…. But it’s there” (49). The nature of bureaucracy appears to be one where its mission, its raison d’etre, becomes subservient to the bureaucracy’s survival. Large bureaucracies begin life as a benign limb of an organism, but somehow evolve into their own organic being, naturally believing their existence is at least coequal to their supposed objectives. Moreover “taking care of the human environment is marginal to the missions of most government agencies” (71). So how do you make bureaucracy/agencies involved in enforcing environmental and cultural resource management more likely to observe the intent of a regulation? Do you try to incentivize agency employees towards critical evaluation of projects rather than rubber stamping them? Could you imagine a situation where cash incentives or promotions were based on the amount of the environment, or quantities of cultural resources protected? How do you quantify the amount protected? By the amount of projects denied? How political feasible is that?

The work of the staff involved in such an agency is necessarily going to be adversarial and contentious. I think one way to encourage, inspire, and insulate them from demoralization, negativity and tendencies toward being coopted or swaying under pressure is to train them for those situations. Have part of their training be simulated situations where employees come under pressure from entities advocating for their project, or from the browbeating executive or the angry landowner who wants to fill the wetland. Though, as King suggests, change has to start at the top with leadership, so how do you ensure leaders are going to be independent and insulated from political machinations? Make the head of the EPA a ten or twenty year appointee instead of a regular cabinet term? But what if the “wrong” person gets the job? And isn’t political pressure on agencies a double-edged sword. If we like that the Obama Administration ordered the Drug Enforcement Agency to deprioritize laws outlawing marijuana use, or Governor Brown’s order not to involve federal authorities in the legal status of those arrested for minor crimes, don’t we have to be accepting of a Bush Administration that deemphasizes enforcement of environmental laws? In a related theme, doesn’t leadership have to be evident at the highest level of our government? Could you imagine a scenario where a sitting congressman illegally fills in federally protected wetlands, initially refuses to pay the fine, eventually begrudgingly pays a reduced fine, and then the citizens of the state elect him governor. Imagine!

King does allow that as much as he points the finger at Bush, he saw the trend away from protection start under Clinton, so maybe our government, on the whole, reflects what the majority wants? A smoke screen of concern and decency, an alleged adherence to some moral standard in our environmental conscience while in reality, once our economic welfare isn’t overtly threatened, we will continue to overconsume, under reuse and reject renewable energy. Environmental and heritage protection are public goods and we care more about our individual goods, therefore we won’t act effectively until our individual immediate welfare is affected. Just as we found when the price of gas hovered around $4 a gallon, consumption went down, sales of large vehicles declined and investment in renewable energy increased.

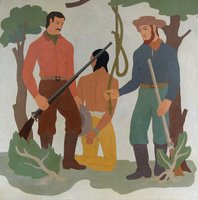

It was interesting to note the cultural difference between government agencies and Native Americans, who see the land itself and not necessarily items manufactured by humans as important. According to King “the tribe said that the Bureau of Land Management was missing the point. It’s the whole landscape that’s significant to us, you see, not just these individual locations that the archeologists like” (78). Likewise, consultation “is not something that most agencies or project proponents do willingly or well,” making me wonder if it isn’t so much the path of least resistance in play here, but a Western ethos of supposed efficiency in getting things done, action over talking (110). In this mindset talking is seen as an impediment to progress, perhaps even a weakness. Not only do “Real Men” not reconsider, they also do not consult. They just fill the damn wetlands in.