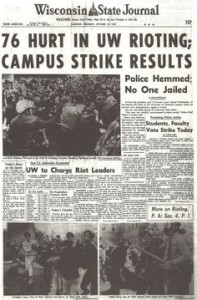

The career path I selected was archivist, as I am fascinated by the preservation of historical records. An archivist is an individual in the field of history who is responsible for the preservation of historical records. They must also arrange these records, insure their descriptions are known, and provide access to anyone who needs to see them. Archivists’ work with records is a process from acquisition, creation, and protection. Archivists are skilled in appraising and cataloging records for permanent storage and retrieval. These people specialize in maintaining numerous records, either if they are still being acquired or just being preserved. Most archivists choose this career path after getting an undergraduate degree from college. The expert I interviewed, Layce Johnson, the Processing Archivist at the Idaho State Archives, said, “I did not take the most direct route to my current position as Processing Archivist for the Idaho State Archives. I realized my love of working with primary source material while a graduate student at King’s College London.” Lacey completed a Master’s in Biblical Studies and then moved to Idaho where she worked in the private sector. As a volunteer at the Idaho State Archives, she gained valuable experience and said, “When a support position opened up I applied for the position to get my foot in the door. I steadily worked hard and moved into different positions along the way.” In 2015, she took the Academy of Certified Archivists exam and became a Certified Archivist. Volunteering, such as Lacey described, as well as Internship opportunities can be pursued during undergraduate and graduate work and are an excellent way to become familiar to the staff. You can advance opportunities to work in the field of history or at historical sites by becoming involved in historical societies and attending association conferences. The wide variety of project types that archivists are known to work on include preserving historical records of all kinds, such as photographs, documents, and government records of a state or country and any collection of historical significance. Archivists work to carefully preserve data and documents so people, either in the field of history or other academic fields, as well as the public, can later obtain the information for a variety of reasons. For example, genealogical research has become a huge area of research by both individuals and corporations alike, which has prompted request for birth and death records as well as marriage certificates to establish familial connection. Besides other archivists, archivists tend to work with curators, museum technicians, museum staff, librarians, and conservators. When asked about the kind of people she works with, Layce replied, “The Idaho State Archives serves the citizens of Idaho as the official repository of permanent and historical records of the state. We serve a diverse community as well as national and international researchers. We serve everyone from retired genealogy researchers, local historians to law firms and legal researchers. People of a diverse socio-economic background utilize our resources.” The projects are as varied as the individuals who pursue this career path, but archivists are detail-oriented, patient, and passionate about history. When it comes to choosing a project to work on, archivists can either pursue individual projects, or the government entity or historical society or museum they work for chooses their projects. Layce described the focus of her job. “As the Processing Archivist I focus on processing projects. Processing is the act of arranging and describing archival materials while maintaining fundamental principles such as Original Order and Provenance. The final outcome is a finding aid, which is a tool for researchers to learn what the collection consists of and leads the researcher to accessing the material.” Sometimes a particular historical society or government employer decides the project for the archivist. Layce is lucky to have some autonomy to “prioritize projects as long as they fall under our agency’s mission and our annual goals.” She works in conjunction with the Administrator for the Archives to choose projects. She said, “Processing projects are ongoing and part of my general function as a Processing Archivist.”

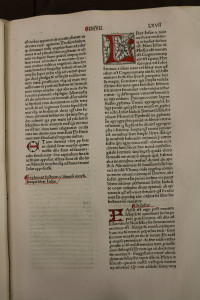

One of the current issues that I have noticed in the field of history would be the advancement of digital technology that has opened up many avenues for archival storage, exchange and retrieval. Layce talked about current problems they face at the Archives. “Our current issues as a government records archives primarily involve funding, resources and advocacy. Throughout the archives profession we are now dealing with the electronic records issue. Many contemporary records are digitally born and require a higher level of monitoring to maintain digital preservation as technologies rapidly change and as equipment, file types and software evolves and some becomes obsolete. This is our new greatest challenge for long term preservation of information, storage and access.” Different archival traditions have been developed in close relationship with the history, court system, and cultures of particular countries or regions.

Encouraging and helpful, Layce answered my question regarding entry level applicants by replying, “Problem solving, critical thinking, attention to details, communication, general knowledge about archives. Often times we look for applicants who have previously volunteered or interned at an archives.” The skills that most entry-level applicants of the archives require are people who can work both on their own or as part of a team; they need to be individuals that can exercise research and writing skills very efficiently, pay close attention to every detail of data or materials, must be excellent problem solvers, and have a passion for history and historical preservation. Many archival positions require people who can work on databases, convert pictures and words into digital form, and work on electronic data-keeping such as websites and other social media, so having a background in working with computers and other electrical devices is invaluable. According to the website www.recruiter.com/salaries/archivists-salary, archivists make roughly about $32,000-$48,000 every year, depending on their starting position and level of responsibility. The salary widely depends on education and experience. Layce said there is a wide range state to state and, “it depends on the type of archives whether it is a corporate archives, academic, non-profit, religious, or city/county/state/federal government archives.” A position currently advertised with the University of Oregon for a Lead Processing Archivist, Special Collections and University Archives has a salary range of $55,000-$63,000 per year. The career (http://hr.oregon.edu/carers//). The government of a state usually fund the state archives, as well as entities like a state historical society and, in Idaho, the State Preservation office and museums. Layce’s response to funding was, “My position is funded by the State of Idaho, some positions are funded through earned income, but are classified differently.” Private companies also employ historians and archivists for positions at their businesses. It is typical for positions in history fields to be funded by the government, as the state history would be lost without money to fund protection of historical documents. With any business, the higher the education, the better when it comes to the job market. Master’s degrees in history are usually appropriate for entry level into the archives. For higher positions, experience of three to five years of experience will be needed. Master’s degrees in the required field are the proper key to gaining the right position, usually a degree in history, political science, library science or information technology. Layce believes that a “Master in Library and Information Science (MLIS) with an emphasis on Archives is the most marketable degree to have within the archives profession. However you can find ways into the field with a master of arts degree in a history related subject.” She said that the profession has become very competitive for even entry level positions. She strongly suggested the MLIS degree stating that it, “opens more doors, because you can go the academic archives route. There is an longstanding and ongoing debate about archives vs history related degrees. There are pros and cons to having one degree over the other. Some archivists end up having one of each.” As Lacey suggested for people interested in an archivist career, study hard and obtain the best possible education. People in the field of history should become involved in historical societies and attend conferences to network. Be prepared for starting an entry-level position and working your way up as experience is gained, which is the path Lacey took in her career. The job outlook for archivists, curators or museum staff was estimated at a 7% growth rate for the 2014-2024 projection, according to https://www.bls.gov/ooh/education-training-and-library/curators-museum-technicians. Layce’s advice to people interested in history, “I would advise people to volunteer and intern at a variety of different types of institutions to get a feel for the profession and gain some real world working knowledge.” Her strongest advice was to research the profession and “understand current professional standards as well as the history of the profession.” She also gave some excellent advice about what it is like working in an Archives. She said, “Sometimes people think of archives as quiet places where they can retreat in the back and work with materials without interacting with the public or people. This couldn’t be farther from the truth.” That was actually a bit of a surprise to me as I did have that impression after having completed an internship at the Archives, but then I remembered that there were many staff members and they were assisting customers and other agencies while I was quietly working on projects. Layce’s information was very helpful and informative in looking at the job of Archivist.